Jesper Grimstrup kindly sent me an electronic copy of his new book, The Ant Mill. He was also kind enough to give me some feedback on a first version of this review.

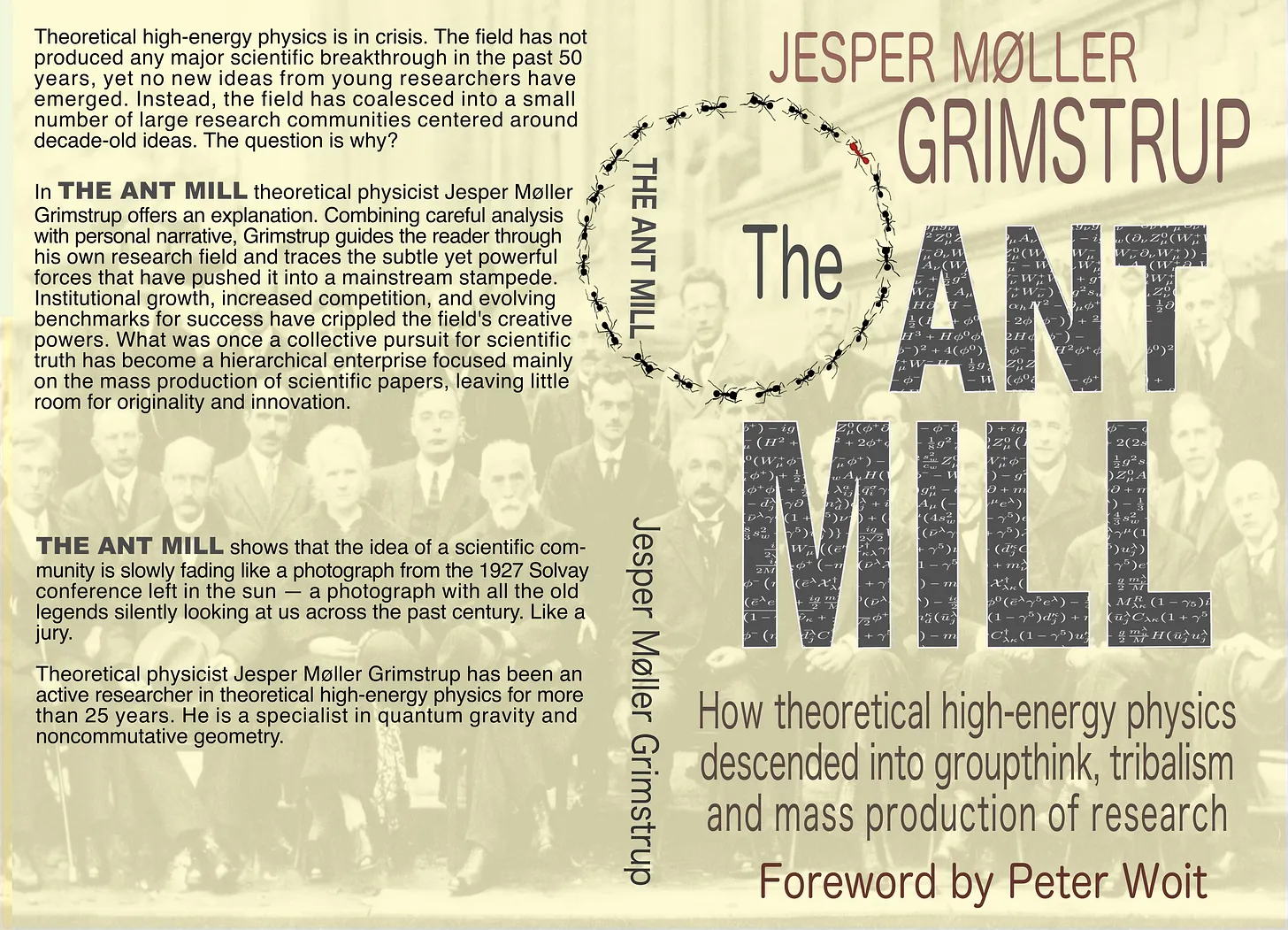

It has a foreword by Peter Woit, who has commented briefly about the book

on his blog; the author also has a

substack. The subtitle is 'How theoretical high-energy physics descended into groupthink, tribalism and mass production of research' so you would expect it to be the sort of thing that I would take a strong objection to. However, I am the sort of person who likes to read things that challenge me; the only thing that gets under my skin in this book is attacking the whole of academia in public.

The story is an interweaving of the author's personal experiences in academia with his general observations. This personal story and his experiences are interesting, much like I expect those of everyone who has spent several years in academia would be. And he has clearly spent a lot of time thinking about thinking about research. I love meta-activities of this sort; the best example that I know of is You and Your Research by Hamming, which I stumbled on as a postdoc. Indeed, the existence of these sorts of things that are shared by young researchers is actually evidence against the central thesis of Grimstrup's book.

The market attacking High-Energy Physics seems to be burgeoning. On the one hand Hossenfelder believes that we have become 'lost in math,' and on the other Woit believes we are not mathematical enough; both attack string theory as a failed program. Grimstrup's book is in the mathematical camp, with the novelty that he piles scorn on all popular approaches to quantum gravity, in particular loop quantum gravity and noncommutative geometry, since he has come into closest contact with them. His observations about string theorists are mainly about the shoddy way that he was treated during his time at the NBI, with several egregious examples of bad behaviour. We are lead to conclude that it is not just string theorists who have formed a closed tribe, but that there are several such groups crowding out innovation.

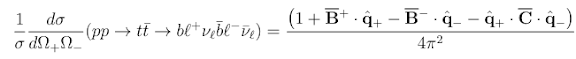

Grimstrup refers to his own research program and gives examples of how it has just generally been ignored within academia. For example, he starts the book with a copy of a grant application by a 31-year-old Niels Bohr for an entire institute, and contrasts this with a grant application of his that was refused that effectively ended his career within academia (my understanding is that at the NBI in Copenhagen it is common to ask for and obtain grants to pay your own salary and prolong temporary contracts). He writes that he does not do this to compare himself to Niels Bohr, but inadvertently this is the impression I got from the book -- that he was doing this not in a self-aggrandising way, but in the sense that you can almost feel his frustration coming through the pages that his expectations did not meet reality. It seems like bait at times, inviting anyone who disagrees with the general thesis to attack him personally. Instead, I will have a look at his papers with an open mind, after writing this review, and keep my thoughts on them to myself.

The book made me think of how many of us enter academia. We grow up reading popular science accounts idolising physicists from a century ago. And it made me think more of the self-actualisation messages that were rammed down all our throats in the popular culture in the 80s and 90s: follow your dreams, stick to your principles, be true to yourself, this is the most important thing in life and you shouldn't worry about money, just be happy. And: working hard and getting good grades is the way to get to the top. The problem is that this is largely obsolete: it's based on the world that existed post world war two when there was a scarcity of labour and an economic boom. Then -- if you were from the right background and your face fit -- you could work hard, get a PhD and walk into a permanent academic job (yes this is a caricature). Science was respected and so were scientists; high-energy physics was at the top of the tree because of the connection with technological advancements and nuclear weapons. That world doesn't exist any more; while in many ways for the better, it is undeniable that we live in a world of much greater competition and public skepticism about science is increasing.

The scientific community has expanded, as has the population; and more importantly education throughout the world and global travel and communication has meant that the number of people around the world who are involved in research is much greater than it was. Grimstrup notes that increasing the size of the academic community has led to fundamental changes of behaviour: professionalisation of research and group think, and that this leads to an increasing incentive to work on mainstream topics. He has done bibliographical research to demonstrate this (in papers and presented in the book). It is clearly true that the Matthew effect exists in many branches of society, and therefore also in academia; governments wanting to exert some form of oversight in exchange for the funds that they provide has definitely led to changes in incentives for researchers. One aspect of this is that it is hard to judge the work of people from other fields, but we are required to do so; and then it is difficult to argue with quantitative measures such as number of papers, citations, h-indices. Then of course the measure becomes the target for certain people.

Grimstrup rails against all these changes; he clearly believed that the correct thing to do for an aspiring researcher would be to work on their own ideas, stick to their principles and not compromise. They should work for a long time, in isolation, on a major paper, put it on arxiv.org and the next day their colleagues would read it and ask interesting questions about them. Fame and fortune would follow. The thing that shocked Grimstrup was that not only did people not even care about any papers he posted, a young competitor even once told him some ideas are simply not worth pursuing even though they may be interesting. For sure, this is horrible and shocking behaviour, and does not reflect well on the anonymous person who said it.

For my part I am still naive enough to think that if new ideas are good, someone will

recognise them as such, and network effects will make them known. I know that many researchers already think

more deeply about what they are doing than he gives us credit for: and

we discuss it, during seminars, over a drink with colleagues, in the coffee-breaks of

conferences, during our annual or five-year reviews, or in grant

applications. When I discussed this review with a string-theorist colleague they remarked "of course we know the situation sucks!'' I

think Grimstrup is therefore wrong to tar everyone with the same brush: the

diversity in our community has increased greatly with

time, and this means that there are indeed strong incentives to take a

risk on a novel idea, because the rewards of opening a new research direction are immense! Being the originator of an idea, or the first to recognise the merit in even an old forgotten idea, can yield tremendous results and even greater recognition nowadays thanks to the same effects. Hence, starting a new field, or even a subfield, is something that most researchers aspire to; the rewards for doing so are even greater now than in times gone by, and the evidence that this is possible is even given in this book: the existence of several communities working on different approaches to quantum gravity. He argues that these are now old and stale, but my point is that the way that they were able to take root at all is an example of how this can happen. There are many subfields that have sprung up more recently, and in other branches of HEP there are of course many examples. Nowadays things can change very quickly: a new good idea will be very rapidly jumped on once it is recognised, and people are constantly on the lookout.

Grimstrup also, like Lee Smolin, divides researchers into visionaries and technicians. He then complains that the technicians have taken over, with lots of disparaging comments about them digging endless holes. He then complains that there is an incentive to collaborate in modern research, only collaborators survive in the system: he has evidence that being a lone wolf is a poor survival strategy. He believes that we should work on our own; yet at the same time visionaries need to collaborate with technicians. I found this very jarring. Other than the facile placing of people into boxes, he is overlooking the benefits of collaboration -- his opinion is that it is just about inflating the number of papers one person can sign (and for sure there are people who cynically do this). But to me, discussing with other people, even just explaining something, is often the quickest way to generate genuinely new ideas or solutions to problems that we may never have come up with alone. At the same time, there are plenty of people who do write papers alone; to take a leaf from his book and share a personal story, I once had a comment on a postdoc application that I had no single-author papers and therefore did not demonstrate independence. Hence, there are incentives and a good reason for young researches to work alone sometimes. I then wrote a single-author paper, as I have occasionally done since (and got the fellowship next time I applied); I would agree that there is a pleasure and some advantages in doing this, but to do this all the time would mean I would risk missing out on lots of new ideas and other perspectives, as well as the pleasure of regular interactions with collaborators, and it would also limit the scope of my projects, where I benefit from others' expertise. Or collaborations may just be working with a student, pursuing my ideas (hopefully they contribute some of their own!) and imparting my knowledge in the process. This is why I do not think that encouraging people to predominantly cloister themselves away to work alone for a long time is the most productive or healthy one.

The book also has a very narrow focus as to the goal of high-energy physics. For the author, the quest is a "the next theory," but in essence this means a theory of quantum gravity, which he acknowledges would be far from being able to be tested with any present or near-future data. Otherwise, we should look for a mathematically rigorous definition of quantum field theory; he hopes these will be one and the same thing. This latter problem has proven to be both very hard and not obviously useful -- it is certainly not obvious that the solution should even be unique, for example a theory of strings would cure ultra-violet divergences, and the question of whether strings should be necessary for such a theory is one that I know people have tried to explore. I also recently attended a talk by Michael Douglas where he reviewed recent attempts on rigorous QFT, so it is a subject that is regarded as important but very difficult, and still being explored by a small number of people. Regarding quantum gravity, some people in the community have taken the opinion that if you have no data, it is not a good problem, and are working on other things. Or people try to make contact with data using e.g. EFT approaches to measuring quantum effects of gravity. The string theory community might say that we do have a theory of quantum gravity, in fact we have a landscape of them, and try e.g. to use it to answer questions about black hole information. But at the same time some people then complain that the leading string theorists have moved on to other things: there are lots of important open fundamental problems, and we just do not know how they are interlinked, if at all!

Grimstrup's insistence that the solution to what he sees as problems is to

shrink competition and also encourage research outside of academia,

reminded me of another Dane, subject of another book I read recently:

king Cnut, famous for (presumably apocryphally) standing on the beach in

front of his ministers and commanding the tide to turn back. Otherwise

Grimstrup hopes for a crisis, perhaps one provoked by his book. He explicitly states that he does not want to fuel the anti-establishment or ant-academic movements, but I

suspect that the only crises we might suffer would not be good for the

field. Perhaps one is already taking place in the US; perhaps people

will take his message to heart despite his protests and start a DOGE-style decimation of

research. Necessarily, in science we mark our own homework: only other scientists

are capable of judging the claims of their peers. If we start opening

this up to question then we will only end with government appointees

deciding what are acceptable topics and directions, or shutting public funding down altogether. What would be left over would surely be even greater

competition for scarce resources.

For me, the solution to the problems in the book, to the extent that I agree with them, is to regularly remind ourselves that we should always maintain a childlike curiosity and not close our minds to new ideas and new possibilities. This is the message from the text of Hamming, and very well put in the writings of Feynman (who Grimstrup bizarrely dismisses as a technician compared to Bohr). Otherwise of course in science it is necessary to have a community spirit, to realise that we are all trying to make progress in the best way we know how, and to help each other do so; and it is necessary to maintain healthy competition as a motivator. But both conflicting instincts -- to compete and to group into communities -- are vital parts of human nature and denying this has been the mistake of utopians throughout history.

I am also sure that many of the complaints that Grimstrup assigns to high-energy physics could also be applied to society more generally. So instead of trying to hold back or reverse the societal changes of the last century we should try to work with them as best we can. We have to accept that we live now in an attention economy; and this gives new opportunities: blogging, social media, writing articles in science magazines or popular press, etc. Since Grimstrup is now, interestingly, an independent scientist, perhaps tying his own research program so closely with his book is embracing the modern world at last, and creating a brand as a radical outside thinker, that will be attractive to private backers. He promotes the path that he has followed, crowdfunding his research or seeking support of patrons, as a possible path for the independently minded once they have completed their training in academia, and in this I wish him well: he is clearly serious, determined and sincere. But while this is now part of twenty-first century society, many people have noticed that this modern trend is a return to the nineteenth century (or even earlier, e.g. Leonardo da Vinci being invited to France by François 1) where a wealthy patron was the only source of funding.